Full post on medium |

Axios write up |

Code on github

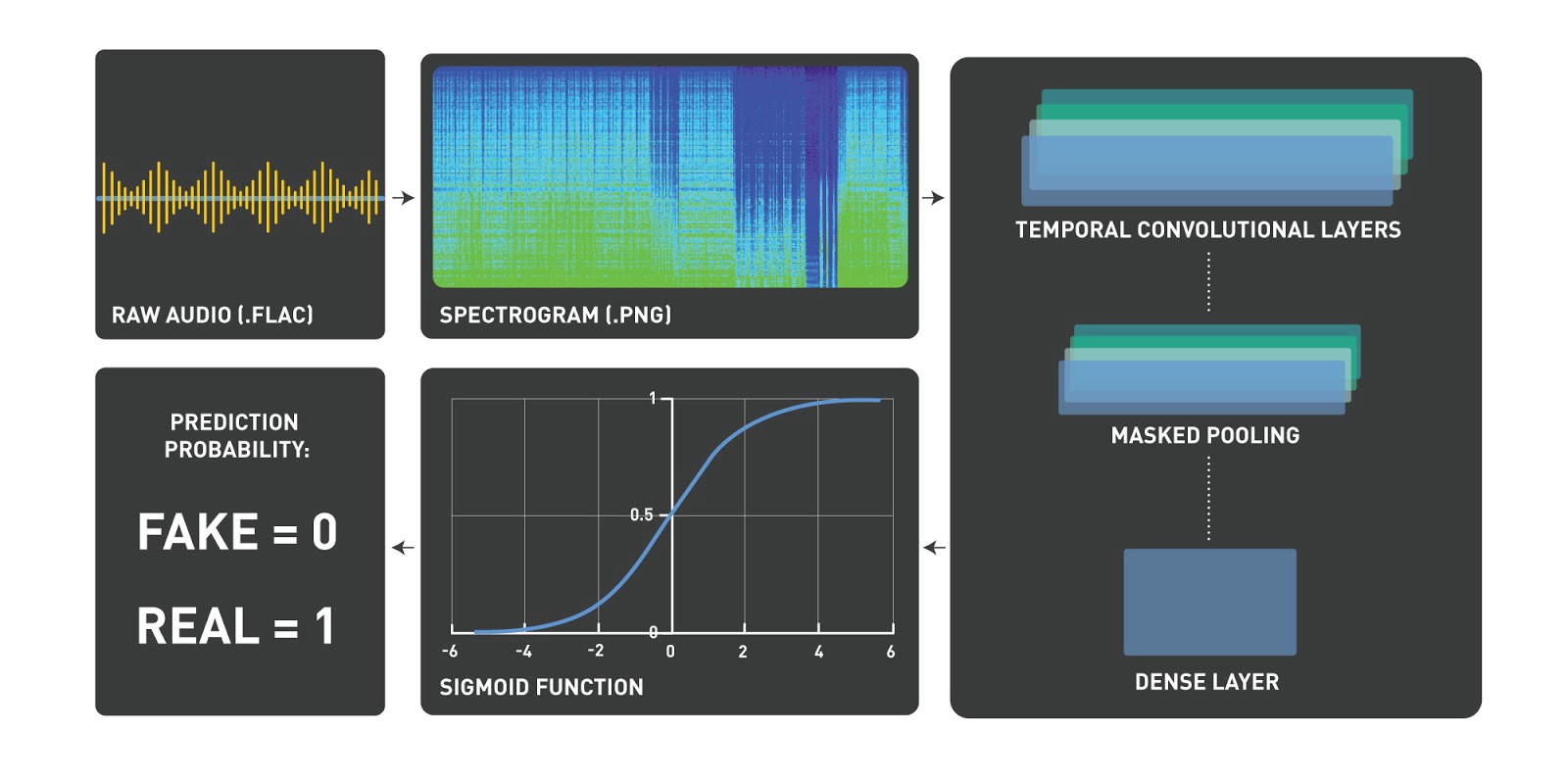

A few of my Dessa colleagues and I released a fake voice detection model. Kaveh wrote about it in this weekend’s Axios’ Future. One of the primary questions throughout this project was asking can “can detectors keep up with new fake voice models?”

The short answer is that it’s going to be an uphill battle. To help with this we’re sharing our code to encourage the ML community that this type of work is necessary.

One optimistic idea from this experience: the effort needed to build detector models is much less than creating them. If we motivate developers of generators (good actors) to build detectors as well, the additional time cost is minimal!

One pessimistic idea: any good detector model can be used to make an opposing generator model better. This cat and mouse game will continue.

An overview of our supernova classification system that we built using data from the Dark Energy Survey.

Betakit write up |

Full post on medium |

Code on github

Combining their interest in space with an exploration of deep learning’s potential applications for astronomy, 3 of Dessa’s engineers have collaborated on a project called space2vec since summer 2017.

Recently, the team built a deep learning system that identifies supernovas from telescope images with record-breaking speed: cutting the time it would take astronomers to identify supernovas almost in half! Here’s the team’s personal account of how they did it.

When we think about languages and how they evolve, it’s usually at the needs of the people that use them. If we want to share a bit of information, whether that be an emotion, or description — we can create a new collection of letters to form a new word. As long as another person has a common understanding of this combination of letters, we can now use our new word in sharing information from one mind to another. Languages can be pretty neat this way, and can get even more descriptive if we talk about emojis.

Software, on the other hand, has overhead and accessibility issues. Sure, it also allows you to invent new meanings, and even create new languages — but currently it only evolves when you tell the machine to do something specific, and with correct details. This makes it tough for most to get involved and interested in seeing how the web, and computers will shape publishing going forward.

Max Bittker and I were lucky enough to spend the last weekend in June on...

How do principles become timeless?

When I discovered Strunk and White’s (1920) famous The Element of Style in school, it provided one of the best lessons in brevity I’ve experienced. I still keep it in mind whenever I’m asked to write, because its concise points are timeless––timeless in the sense that while it is about style, it is not binded to style. Strunk and White’s style guide is still incredibly in-touch with writers almost 100 years later.

So I was happy to find this book, a derivative of the famous Strunk and White book, The Elements of Programming Style by Kernighan and Plauger, written in 1978, close to 40 years ago.

TEPS uses Fortran as its example language, but much like the book that inspired it, the lessons it teaches are timeless and still hold up today. When you can distill rule and opinion to good practice, you can advice that lasts a longtime.

I don’t think it’s quite right to call either the English, or programming style guide timeless, but it’s still evidence...